25

Aug

2014

Distracted Driving — Current Case Law

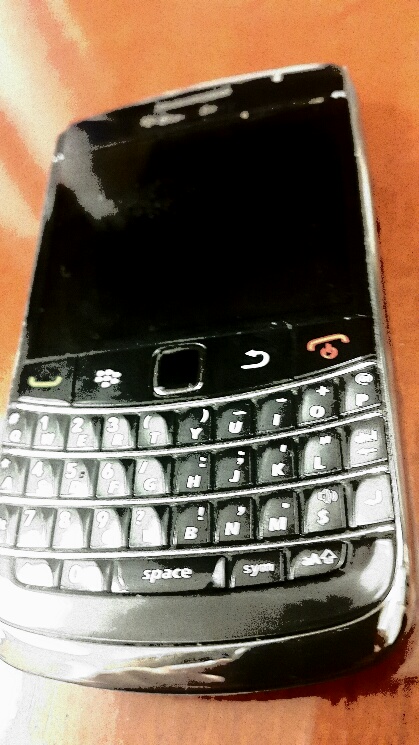

In December 2012, I wrote an article on the case of Farnworth v R [2012] Bda LR 44 (151 KB PDF). This particular case provided guidance on the definition of a hand-held device which was in use while driving. Furthermore, it illustrated that the definition of ‘use’ with regards to a hand-held device was quite wide.

In Bermuda, the law that guides the use of hand-held devices while driving is regulation 44 of the Motor Car (Construction, Equipment and Use) Regulations 1952 (the “Regulation”). This Regulation has once again come under judicial analysis in the recent case of Lincoln Raynor-Saldana v The Queen [2014] SC (Bda) 58 App (262 KB PDF).

This particular case was an appeal from the Magistrate’s Court of Bermuda (Criminal Division) wherein Mr. Raynor-Saldana (the “Appellant”) was convicted for using a hand-held cell phone, namely an iPhone. Mr. Raynor-Saldana was fined $400 and given six (6) demerit points.

In December 2012, I wrote an article on the case of Farnworth v R [2012] Bda LR 44 (151 KB PDF). This particular case provided guidance on the definition of a hand-held device which was in use while driving. Furthermore, it illustrated that the definition of ‘use’ with regards to a hand-held device was quite wide.

In Bermuda, the law that guides the use of hand-held devices while driving is regulation 44 of the Motor Car (Construction, Equipment and Use) Regulations 1952 (the “Regulation”). This Regulation has once again come under judicial analysis in the recent case of Lincoln Raynor-Saldana v The Queen [2014] SC (Bda) 58 App (262 KB PDF).

This particular case was an appeal from the Magistrate’s Court of Bermuda (Criminal Division) wherein Mr. Raynor-Saldana (the “Appellant”) was convicted for using a hand-held cell phone, namely an iPhone. Mr. Raynor-Saldana was fined $400 and given six (6) demerit points.

19:17 /

Litigation & Dispute Resolution

On June 10 2014, MJM Limited presented to

On June 10 2014, MJM Limited presented to